By Rhia Grana, June 21, 2022; ANC

“If you’re looking for beautiful 19th century houses, you can find them in the District of San Nicolas [in Manila],” says heritage conservation advocate Dr. Fernando Zialcita. He’s talking particularly about those built in the late 19th century. “It’s a boom that involved not only the Chinese mestizos but also the Filipino bourgeoisie.”

Vigan may be known for its grand Spanish colonial houses but when it comes to refinement of details, in terms of exquisite woodwork and grillwork, San Nicolas can’t be beat in Zialcita’s book. “Actually, the houses there are more beautiful than elsewhere in the Philippines, because this is the capital city we’re talking about.”

Structures that come to mind are the ancestral homes of General Antonio Luna along Urbiztondo Street and the ancestral home of the Sunicos on the corner of Jaboneros and Barcelona Streets. The family of Dr. Jose Rizal once lived in a house along Estraude but this was razed by fire.

Many rich Chinese families lived either in Binondo or San Nicolas, so their influence can also be seen in some of the houses in the district. “In the 19th century, when the Chinese were finally allowed to live in any part of the archipelago without restrictions, they began to dominate the local industries like the coconut and abaca industry. The district marks the zenith of Chinese fortunes in the Philippines,” Dr. Zialcita tells ANCX.

What’s more interesting about the district, says the anthropology professor, is that many of its really old houses survived the bombings of World War II—these include structures built after 1863. “Rows and rows of houses laid out in a checkerboard pattern,” adds the cultural historian.

Historic district

Aside from beautiful houses, important public buildings can also be found in San Nicolas. Standing along Calle Asuncion was the Casa Tribunal de Naturales, which used to be the courthouse that served the people of the district. Cases were then presided over by a local gobernadorcillo, and a well-known gobernadorcillo of San Nicolas was the 19th century metalsmith and bell caster, Hilario Sunico.

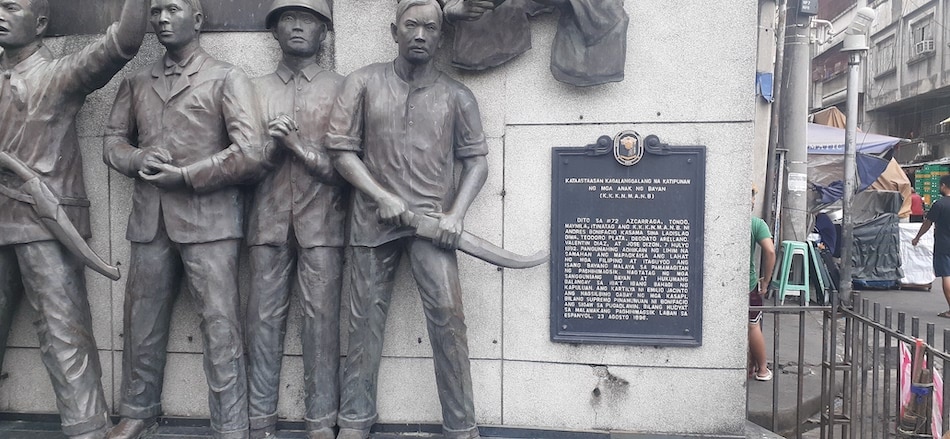

The district also witnessed a nation’s important historical events. The Katipunan’s newspaper, Ang Kalayaan, for one, was founded in a house along Calle Levesares. The structure, however, has been torn down and only a marker of the house exists on the spot.

Meanwhile, on the northern fringe of San Nicolas—on Azcarraga St. (now Recto Avenue) near Elcano Street—is the site of the house where the Katipunan was founded on the night of July 7, 1892. “The Katipunan was not founded in Tondo,” clarifies Dr. Zialcita. “It was founded in San Nicolas.”

Why it needs saving

Unfortunately, not too many people know about the District of San Nicolas. Or that San Nicolas and Binondo were actually part of a single district during the Spanish period. It was split into separate districts at the beginning of the 20th century.

“It has the largest collection of late 19th century houses. But they are disappearing rapidly,” Zialcita observes. Through the years, the district has become increasingly commercialized, and many of the houses have been demolished and turned into high rises.

Which is why Zialcita and Ateneo de Manila University architecture professor Erik Akpendonu devoted an entire chapter about San Nicolas in the former’s book “Endangered Splendor: Manila’s Architectural Heritage, 1571-1960, Volume 1.”

Saving the district needs the concerted efforts of the city government and its people, says Dr. Zialcita. “You cannot have a city na panay high rises lang lahat. You need a livable city.”

To raise awareness about the historical and heritage value of San Nicolas, Instituto Cervantes de Manila headed by its director Javier Galvan recently organized a round table discussion attended by historians, architects, urban planners, businessmen, residents of the area, and the general public. The discussion reflected on the value of the San Nicolas district, explored its potential as a historical site, and brainstormed ideas on how to conserve it.

Zialcita is aware it will be difficult to save the entire district, so what he is proposing is to at least save some of the streets in San Nicolas, citing what was done in Macau as an example. “They saved at least a block, then they let the high rises spring around. That would be a nice compromise,” the heritage conservation advocate says, bringing up the Portuguese settlement, which is now a popular tourist attraction in Macau.

He suggests restoring several blocks of houses and maintaining their beautiful facades. They can use the ground floors as shops, restaurants, and galleries, and the second floors as residences.

To hear him say it, there’s a bigger message here. “Kung ang pag-ibig ay wala, ang mga bayan ay dili magtatagal,” he says, quoting a line from Emilio Jacinto’s poem, “Liwanag at Dilim.”

“He’s correct! If we don’t love our city, or our country for that matter, we won’t survive,” says the cultural historian. “And the way to survive is by knowing the stories connected with our city. Visiting the districts of our city, visiting the different structures, knowing their stories. That’s how you develop love. As the saying goes, ‘Kung walang kuwento, walang kuwenta.’”

[Photos courtesy of Javier Galvan/Instituto Cervantes]